We know the role of academic STEM librarians is constantly changing. As part of this, the role of librarian is expanding beyond just being a curator of books, periodicals and similar content. Many librarians are responding to this shift, becoming more actively engaged in supporting research and scientific reproducibility, and engaging in social media and event outreach, among other tasks (for a few examples, see here, here, and here.)

This new landscape is reflected in JoVE’s recent librarian survey, where STEM librarians discussed a variety of professional topics, including the advantages of having a science degree. From the survey results, it’s clear that science librarians face many challenges in communicating and supporting their various academic audiences. But these are far from insurmountable obstacles, librarians in the field tell us.

Science Degrees Of Separation

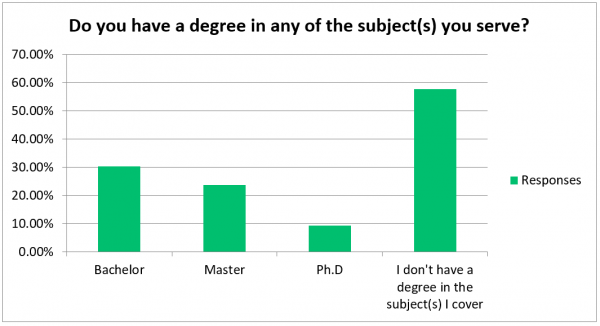

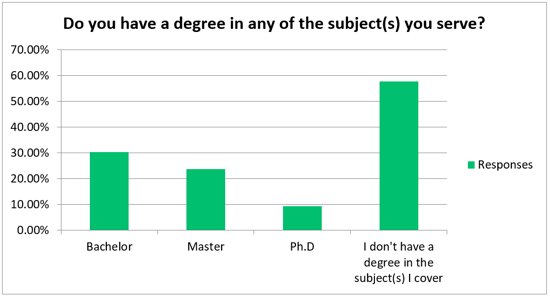

For starters, the backgrounds of librarians and the faculty/students they serve don’t always align. In fact, 57 percent of the librarians surveyed didn’t have a degree in the disciplines they serviced. Of the remaining roughly one-half of the respondents, only 9 percent held science doctorates. Given that science is a demanding taskmaster, this definitely does not help the librarian in understanding the research community’s needs, at least not when the librarian is just out of the gate.

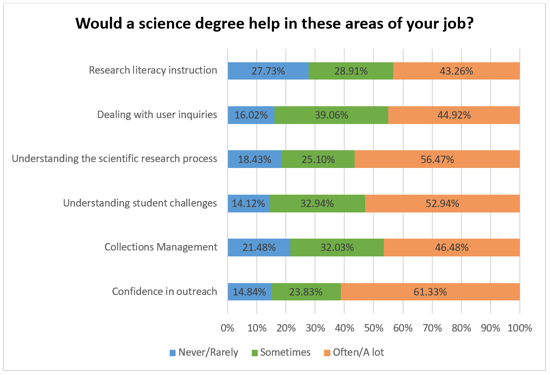

Accordingly, a majority (61 percent) of librarians felt a STEM degree would boost their confidence in faculty outreach. Moreover, 52 percent surveyed also believed that a degree would help them understand STEM student challenges — while 55 percent believed it would aid them understanding the scientific research process.

With/Without Degree, STEM Challenges

However, lacking a degree need not be a deal breaker, explain two professional librarians. “I don’t believe we all need a background in the science subject we cover,” says Alyssa Valcourt, an MLIS Science & Math Librarian at James Madison University. “But we need to feel comfortable in acknowledging what we don’t know about the subject and be willing to learn from faculty and other librarians in the field.”

Also, there is the librarian network itself that can support STEM interaction success. “The science librarian community has been very welcoming and in the past year, has provided multiple conferences that focus on helping science librarians succeed and gain confidence in their job,” says Valcourt.

Another librarian goes further. Outreach to science faculty is the most difficult aspect of the job, even for STEM librarians with science degrees, notes Chemical Information Librarian at the University of California, Berkeley, Kortney Rupp. Being outstanding requires her to understand everything she can about her specific domain. “It's not so much about understanding the science," she says, “it's about understanding how information transfers within that tiny community and how best you can contribute to reducing the burden on researchers in their world.”

Librarians Retain Core Skills

On the other hand, the survey indicated that librarians have well-earned confidence in their training and own skill set. They are comfortable as librarians: only 32 percent believed a degree would even sometimes help their content selection activities. When dealing with inquiries, only 40 percent thought it would assist, even rarely.

“Just like they [students and faculty members] are each specialist in their fields, I am a specialist in my own field as a librarian,” says Valcourt. “There have been many times that I have not felt confident in speaking with faculty or students, for I don’t want them to think I am a fraud. However, I have been trained in the research process, data management, how to evaluate information, provide information literacy instruction, etc.”

However, some STEM-specific insights are in order here, indicates Rupp. “Without having engaged in scientific research, you just don't know what you don't know. If you haven't struggled through a project from beginning to end, how can you even start to have a conversation with those that do it on a regular basis?” Because of this, she suggests any librarian in graduate school (but without research experience) should take on a research project. And a STEM librarian-in-training should focus in the science field and write a thesis, just for the experience.

She speaks from personal knowledge: While working on her library degree, Rupp attended meetings of a veterinary research group to see how it approached experiments and shared data. “The final report that I created made suggestions about how they could do better practices in research data management. I had never been in a lab that worked with mice, so I learned a lot about how that type of research is conducted.”

Filling STEM Gaps

Both Valcourt and Rupp suggest practicing librarians reach out to science librarian specialists, and learn as much as is possible. Valcourt also talks to faculty members to ask questions about their research and their challenges. Another useful practice, she says, is to speak to students to see how they are coming along with their university research.

“Science librarians without STEM backgrounds need to be connected to, and educated by, librarians with STEM backgrounds,” claims Rupp. They should find webinars, videos or workshops on specific STEM topics. They can also bring in speakers that “can provide valuable advice with practical solutions.” But the key, with or without a degree, will be the effort, says Rupp. “Anyone can be an excellent STEM librarian. It's just likely going to require time and effort up front, to understand how things work in the field you are responsible for. Persistence is key.”