There are special areas where, you, the librarian, can help improve the quality of life of students working in various biology, chemistry, engineering and other labs on your campus. To that end, it will help you to understand something of the graduate student’s life, as he or she endures the stressful pursuit of a doctorate.

Focus On Your Grad Student Constituents

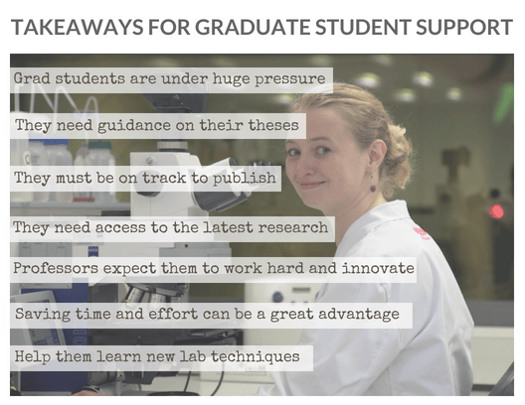

For starters: Those grad students you interact with are almost certainly under a lot of pressure. They are navigating their ways through labs to doctorates, and most likely, towards highly competitive fields in academic or corporate research. (Then again, nobody ever said the road to being Newton, Einstein, or Darwin was easy.)

A graduate student, ideally, will have a strong relationship with his or her advisor (the principal investigator or "PI") and the backing and support of lab colleagues. In that ideal world, the student knows outright —or has a good idea of — where his or her thesis is going.

But don’t count on that ideal world being reality. It’s possible that things aren’t going quite as well the student might think or hope. The student may, with reason, be wondering if he or she is on the right track — because if not, that student’s academic career (indeed later career, too) could be in serious jeopardy.

Plenty can go wrong: If you are working with a graduate student, you may discover he or she:

- Doesn’t communicate with the the PI/thesis advisor well, or at all

- Expects the PI to micromanage all thesis and lab activities

- Isn’t sure how the thesis is going

- Is facing constant experimental failure

Such grad students may have already invested a year or two into the process, and they might be brilliant students, but … .

Life Of PI

By and large, the student is living in the lab, and as the name indicates, the laboratory is a place of work, where the student is an employee. Hopefully, your students have embraced this less-than-glamorous fact: To some degree, they are worker bees, and not just students devoted to the pursuit of pure knowledge. The students must align their goals and methods to the lab’s actual working model. In every business, the worker must meet the goals set out by the superior, all the way up to the CEO. And just as in every other business, not all bosses are created equal.

Principal investigators oversee lab operations, securing grants, publishing, and much more. And usually they get where they are because they’re great scientists, not great managers. So, communication with employees can often be an afterthought, and, chances are, the PI doesn’t see the world as the student sees it. A recent survey cited in “Nature” magazine shows the huge gap between how lab workers view things versus how the PI sees them. This situation isn’t necessarily self-correcting, and the silos remain in place year after year.

“Principal investigators are busy people, and although meeting on a weekly basis at the very least is ideal, it can be challenging to achieve,” says Alisha D., who recently took an engineering doctorate from Dartmouth College. And, she says: “A student might also need to be innovative, think outside of the box, and explore areas that the lab may not necessarily have any expertise in.” And it can be a busy life in the brief time the student spends outside the lab, as the PI also wants the student to be out advertising, at conferences and doing presentations.

Lab Basics?

Moreover, graduate students, as a rule, must become reasonably autonomous in their research. At some point, the PI (if he or she cares actively about the student) wants the pupil to leave the lab’s hive and become independent.

“The goal of the advisor is to transform a student into an independent researcher, but at some level the student has to get it on his or her own,” states Dr. Joshua Semeter, an engineering professor at Boston University. For some PIs, tangible goals are simple and they revolve around peer-reviewed success. “Breakthroughs and publications are not icing, they are the cake,” states Semeter. “There is no point to being a graduate student (at least in engineering or science) unless you are on a path toward publishable results.”

The student may not realize he or she must be hungry for breakthroughs. But the goals are uniform: The student, in fact, may not become an academic rock star — but the PI wants to know the student is trying to become one. Semeter admits there are smaller interim goals: “Yes, there are checkboxes along the way — Ph.D. students must pass a qualifying exam, receive A's in their coursework, and write a formal dissertation prospectus — but, in the end, the metric that matters most is great research, supported by peer review.”

Failure Road To Science Success

It may be a surprise for those who have not worked in a research lab how many experiments go wrong. A student may be on track to innovate in the long-term, but typically, any discovery requires that student to work through multiple failed experiments — sometimes many failures. “The students need to have the ability to reflect and improve their techniques until they find what works — they must be able to have self-learning capabilities,” notes Dr. F., an engineering PI at a Midwestern university. They must have the maturity to tackle the problem assigned and accept experiment failure.

This is just an introduction to some of the pressures bearing down on the graduate student. Bottom line: The STEM business is a very competitive one: Realize that you can help the student with the tools and mindset they need to succeed in it. A librarian can point the student to the most relevant research and protocol methods (available in video and other formats).

In the next blogs, we’ll explore both the challenges your colleagues face, and ways you can help make those an opportunity for your career.